Dear Dawn: The final component of my conversion will be the mikvah. I want to complete this step, but our local mikvah has been closed through the pandemic. Is the mikvah mandated for conversion in Reform Judaism? (I want to do it, whether it’s required or not.) Can I do it in an ocean, with a representative on shore? I am looking forward to the ceremonial solemnity. — Patiently awaiting my mikvah

Dear Patiently: Many people have faced the same problem during the pandemic, and rabbis have opted for an outdoor mikvah! No, mikvah is not mandated for a Reform conversion, but who would want to miss out?

You stimulated my interest in learning some of our local rabbis’ approach to an outdoor mikvah. I was surprised by how many of them do utilize this option.

It is critical that you meet with your rabbi and discuss the details of how the outdoor mikvah will be handled.

Issues include: modesty (public nudity is out); safety (rough waves are dangerous); participants (you will need helpers); clothing (avoid wardrobe malfunctions in the water); ceremony (what exactly will happen and in what order?)

Generally speaking, the rabbis I communicated with look for a secluded location on a beach, away from the eyes of the public. Candidates may wear either a bathing suit or a loose-fitting garment like a robe. Rabbis may ask whether you can swim; they will refuse to put you in danger.

A loved one accompanies the convert to a spot in the surf where it is deep enough to lift your feet off the bottom and dip under the water. Your companion will help you disrobe if you are wearing a swimsuit or want to be naked. They hold your garment while the rabbi calls out to you from the shore, telling you what to say and when to dunk.

After the three dips are completed, your companion will help you dress before you exit the water. Some rabbis have a Thermos with a warm drink waiting. Several rabbis described having family members hold up towels to shield the new Jew as they take off their wet clothes and put on dry ones. Several rabbis mentioned going early in the morning or at sunset to avoid running into others.

Here are some comments I received:

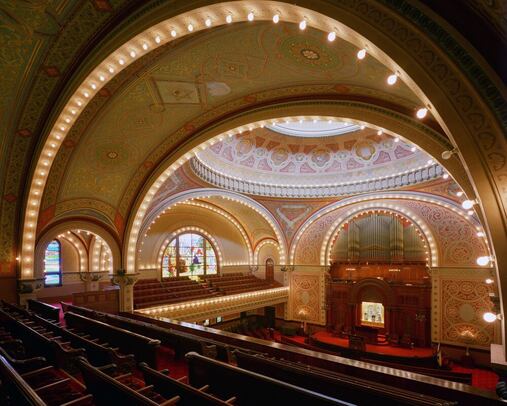

Lisa Erdberg, conversion guide, Congregation Sherith Israel, San Francisco

The people strip down to bathing suits on the beach, go into the water and remove their bathing suits under water. After their immersions, they put their bathing suits back on under water and emerge. We wrapped them in towels to dry off, and then they put their clothes back on. There is a restroom very close by that they can use. They recited the Shema in the water.

My sense is that people have found the water to be very cold, but they are so excited that it doesn’t actually feel cold.

Because it’s the Pacific Ocean, it is cold with choppy water. It’s hard to hear because of the wind. They can only let go of their bathing suits for a second. Immersion in a calm ocean or lake would be a much more tranquil affair and offer more opportunity for intentionality.

Rabbi Jaymee Alpert, Congregation Beth David, Saratoga

Candidates dress in loose-fitting clothes and bring a change and plenty of towels for afterward. They go in alone, just far enough that they can pick their feet up and immerse fully. It is quite noisy with the waves, and I have to listen carefully for the blessings.

Once out of the water, they wrap up in a towel immediately. I think they are very brave. I haven’t managed to put more than a foot into the water. I had to reschedule a conversion because of riptides, so that is also something to be aware of.

Rabbi Gershon Albert, Beth Jacob Congregation, Oakland

Some Orthodox beit dins (rabbinical courts) will allow a conversion candidate to wear a loose-fitting robe or wrap themselves in a sheet when they immerse, protecting their modesty throughout the process.

Rabbi David Booth, Congregation Kol Emeth, Palo Alto

I have them wear a robe or wrap themselves in a sheet when going into the water, and then just put it back on as they emerge. It is true that there are days when the surf is up and it’s more exciting than planned.

Rabbi Jonathan Prosnit, Congregation Beth Am, Los Altos Hills

In a phone conversation, Rabbi Prosnit told me there is a protected cove area at Half Moon Bay that he uses. The candidate goes with a friend or partner, both in bathing suits, into the water. When they have waded in deep enough to disrobe under the water (about 20 yards out), the candidate takes off their bathing suit and dips. He guides them in the traditional blessings from the shore. The individual redresses in the water and comes out to a celebration with loved ones on the shore.

Rabbi Prosnit pointed out that the mikvah preparation of showering, flossing and cleaning under the nails can be very beautiful, but generally is not possible in a beach setting.

Water locations used by Bay Area rabbis include Santa Cruz beaches, the Albany Bulb (which is the end of a landfill peninsula), Half Moon Bay or nearby Mavericks Beach, Lake Anza in Berkeley, San Gregorio Beach (south of Half Moon Bay), and three San Francisco spots: the St. Francis Yacht Club, Aquatic Park near Fisherman’s Wharf and Crissy Field.

This is clearly an individualized process that you must discuss with your rabbi, but the good news is that it can be done.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed